Ask the Developer Vol. 10, Pikmin 4—Part 1

This article has been translated from the original Japanese content.

The images shown in this interview were created during development.

In this tenth volume of Ask the Developer, an interview series in which Nintendo developers convey in their own words Nintendo’s thoughts about creating products and the specific points they are particular about, we’re talking to the developers behind the Pikmin™ 4 game for the Nintendo Switch™ system, which launches on Friday, July 21.

Check out the rest of the interview:

Part 1: ‘Pikmin 1 people’ versus ‘Pikmin 2 people’

Before we start, in addition to the developers behind the Pikmin 4 game, this time we've also invited developers from the first Pikmin game as special guests. I would like to start by asking about the origin of the Pikmin series. Did the series start with Miyamoto-san proposing the concept?

Shigeru Miyamoto (referred to as Miyamoto from this point on): As I recall, Hino-san and Abe-san were initially coming up with a lot of ideas as directors, right?

Shigefumi Hino (referred to as Hino from this point on): That's right, Abe-san and I were directors at the time. Our discussion of this project started during the transition from Super NES (1) to Nintendo 64™ (2), so we had a strong aspiration to utilize its ability to display a large number of characters on screen.

(1) Super NES: A home video game console released in 1991 in North America following the Nintendo Entertainment System™.

(2) Nintendo 64: A home video game console released in 1996 in Japan and North America, and 1997 in Europe. It was the first home console from Nintendo with the ability to display large-scale 3D game environments. The controller was equipped with a 3D control stick that enabled player characters to move around freely in a 3D space.

Masamichi Abe (referred to as Abe from this point on): Hino-san originally came from an artist background, so he was handling character design and world creation, while I was in charge of game mechanics and stage design. This project wasn’t initially an action game, was it?

Hino: Yes, that’s right. Back then, we envisioned a game that would control a lot of characters with AI. The game we had in mind included creatures with AI chips in their heads to make them think a certain way, and you would control them by swapping their chips. So, players would control them by assigning “thought chips,” such as "combat," "heal," or "help friends," to each of them. As they explored the map and gained more experience, their chip capacity would increase. In other words, they'd become smarter. At the same time, we added personalities such as grumpy and cowardly via “emotion chips," and depending on which emotion chip the character had, the response, such as "attack" or "defend," would change. And so, we were experimenting with these kinds of prototypes with Kando-san.

Yuji Kando (referred to as Kando from this point on): I was still a newbie programmer in my first year around that time. After joining Nintendo, I was assigned to this team and got a mysterious specification document from Hino-san, completely out of the blue. (Laughs) I devoted myself to experimenting with what kind of actions I could apply to a large number of characters with AI.

Junji Morii (referred to as Morii from this point on): I joined the team as a designer about a year after Kando-san. By then, the game was already bustling with little creatures.

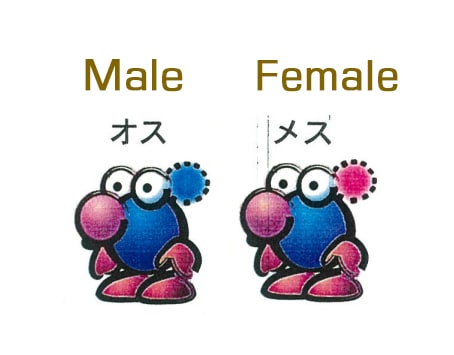

Hino: At the time, our vision was to have a top-down view of the game on screen, so we made the gender and personality of each character identifiable from what's on their head.

Wow... That's worlds apart from the Pikmin we all know.

Hino: It looks a bit Yoshi-like, don’t you think? (Laughs) But we felt it lacked impact as a character.

Miyamoto: There were also conversations about making a character that girls around the age of high school would find cute, right?

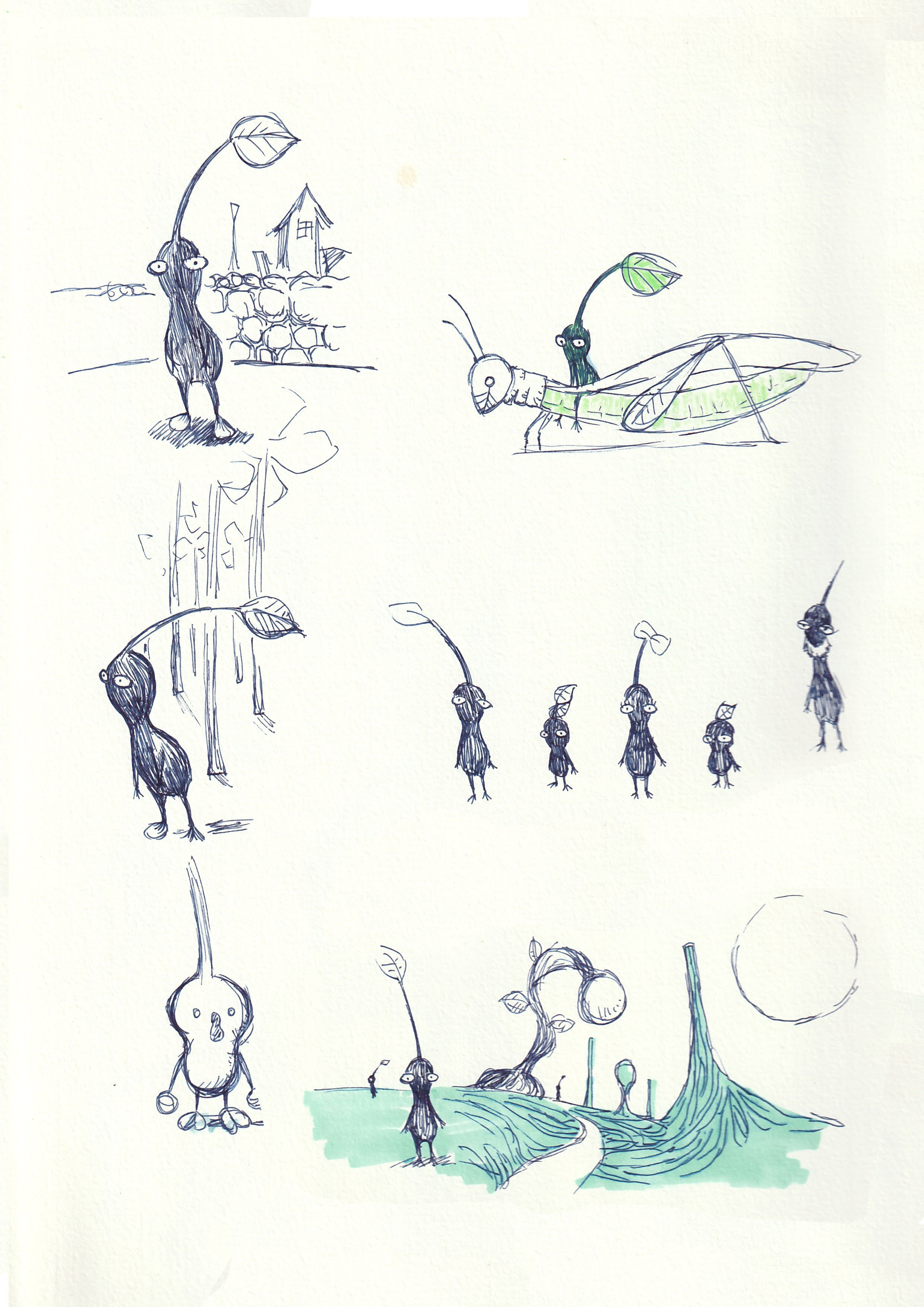

Abe: Yes. So then Morii-san drew a pile of sketches, and this design was selected by unanimous decision.

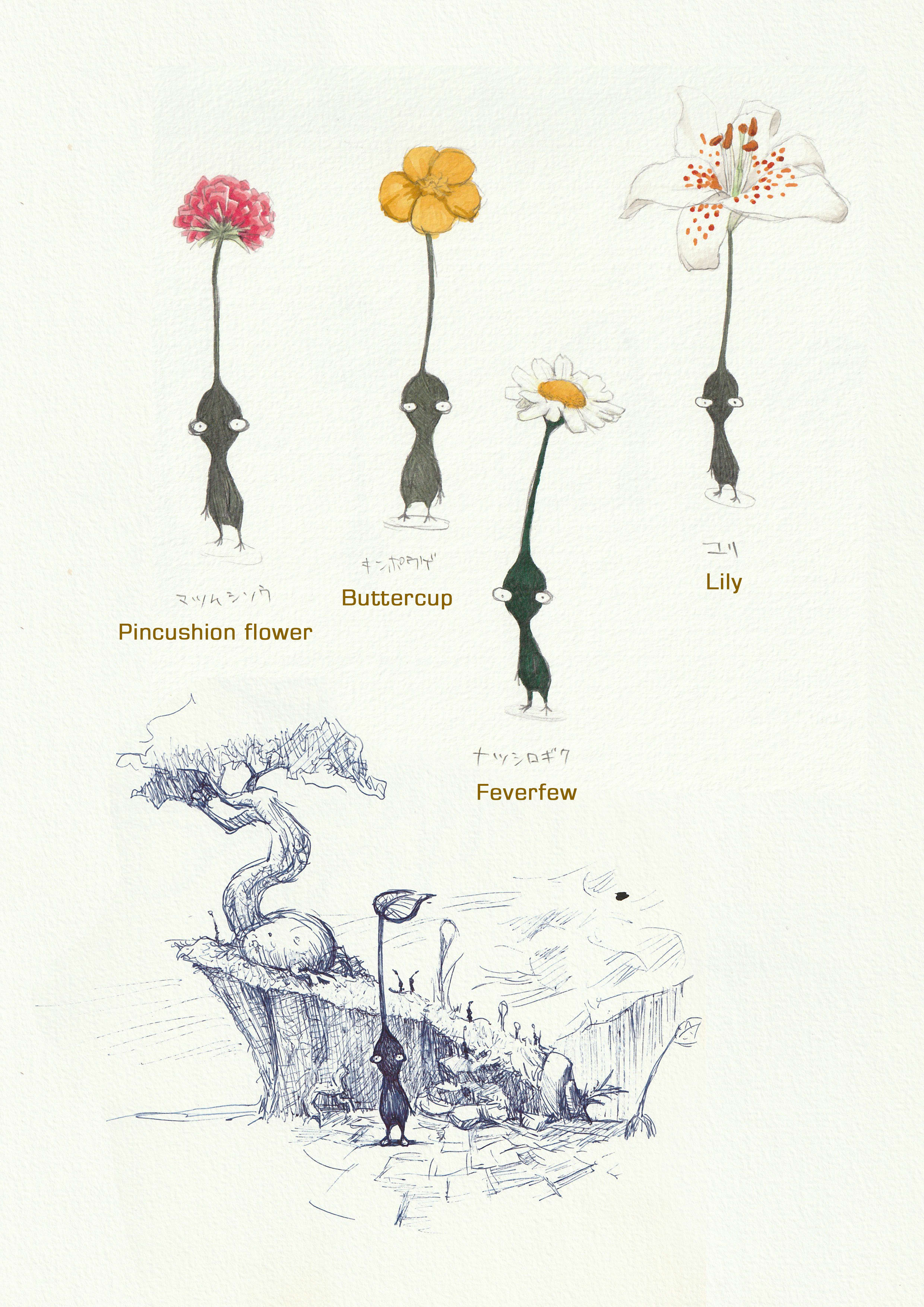

Suddenly it looks more like the Pikmin we’re familiar with. I notice that having a mark on its head is aligned with the initial concept.

Morii: I can’t recall why we put a leaf on its head...but since the character is tiny, maybe I thought that it needed something to help it visually stand out.

Miyamoto: I was strangely attracted to this design. I liked the idea of plants walking. We were saying things like, “It would be cute if it sucked up water from the leaf on its head.”

Was there a particular inspiration that led to this design?

Morii: Back then, I really liked the world of Tim Burton (3), so I wanted the designs to not just be cute, but also give a sense of eeriness, or some emotional weight. That's why I was drawing the sketches like this, with a style that layers scribbling lines.

(3) American film director and film producer. Specializes in drawing eerie but comically designed worlds.

Hino: Nintendo games up to that point were strongly associated with the bright and vibrant designs of the Super Mario™ and the Legend of Zelda™ series. That’s why I wanted to take a bold step and depict a somber, mature, and mysterious world. So, we said, “Let’s watch a movie together for inspiration!” and the choice was an animated movie called Fantastic Planet (4). We all had puzzled looks on our faces while watching it. (Laughs)

(4) An animated movie released in France in 1973, using a production form called cutout animation. The original title in French is La Planète Sauvage (”The Wild Planet”).

This movie you mentioned seems memorable in many ways-the kind that gives you nightmares. So, this was used as inspiration for Pikmin?

Hino: Since we were creating a game that deals with living creatures, we also read a book by Richard Dawkins called The Selfish Gene.

Miyamoto: Oh, I'm not sure I've read that.

Hino: Well, it had lots of information about the weird ecology of living things, so I read it to fuel my imagination. But it was too difficult for me to understand... (Laughs)

Miyamoto: We watched all kinds of films for inspiration, like indie films from Europe or artistic films you wouldn’t find in regular video stores. It was an interesting time with lots of experimental footage coming out with innovative modes of expression, like ones that deliberately layered the same images repeatedly.

Kando: Speaking of on-screen expression, when we were first developing the game for Nintendo 64, we expressed the idea of many characters being there by combining flat boards called billboards to create characters, thereby lightening the processing workload. When the platform changed to Nintendo GameCube™ (5), we were finally able to express each individual character as a 3D model.

(5) Nintendo GameCube: A home game console released in 2001 in Japan and North America and in 2002 in Europe. It is mainly characterized by its cube shape and the adoption of 8cm optical disks for software.

Miyamoto: In the early days of Nintendo GameCube, I also worked with a different team doing various experiments on what’s called Mario 128 to see what would happen if it had over 100 instances of the player's character.

Mario 128 is the tech-demo from the Nintendo GameCube announcement, correct?

Kando: We didn't know about the existence of Mario 128, so it's not like Pikmin was influenced by Mario 128 in terms of planning or technology, but many new ideas came out of Nintendo GameCube's ability to move a large number of characters, which wasn't possible back in the days of Nintendo 64.

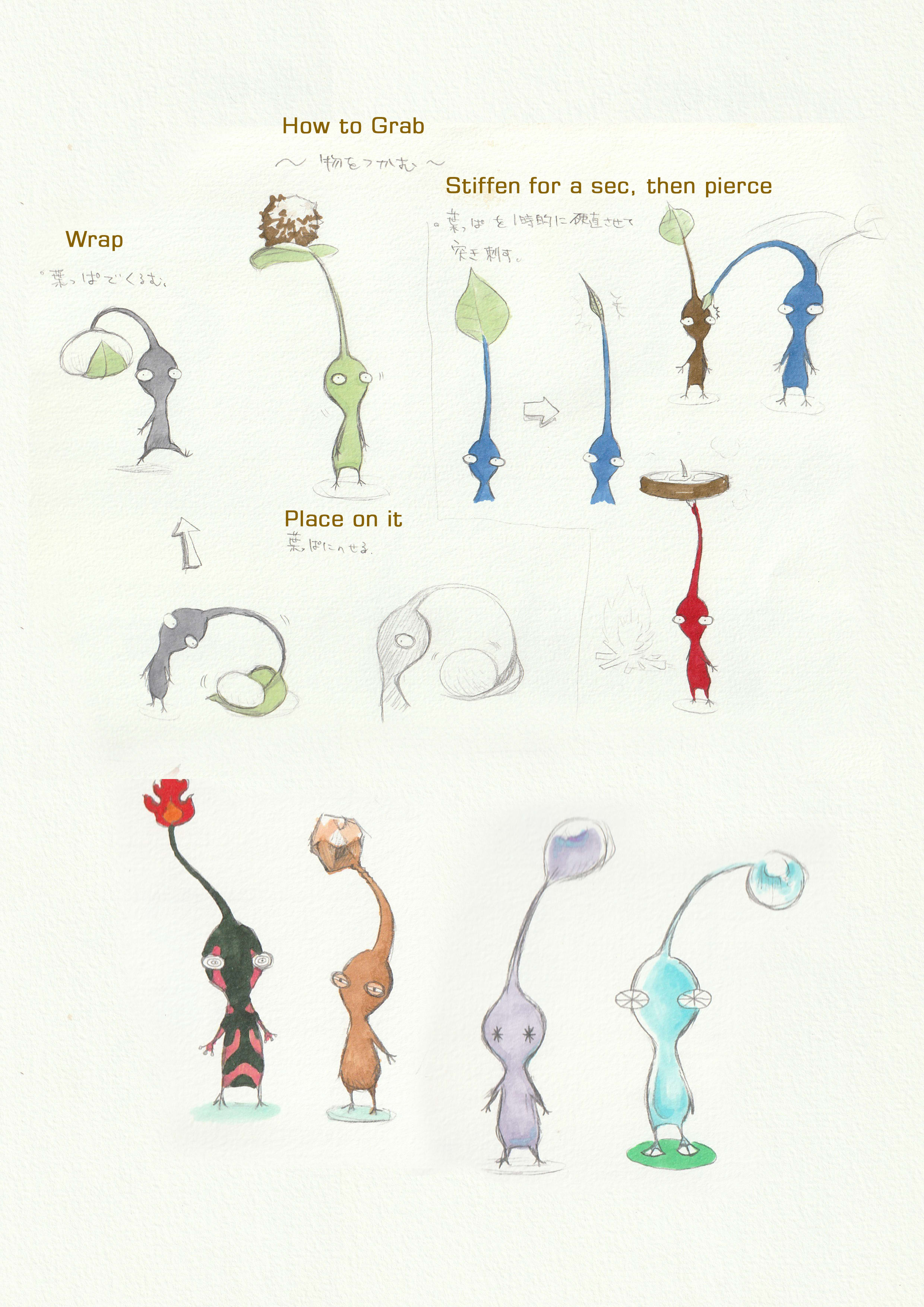

Abe: Once the design had been decided, the game design team experimented with ideas one after another as they came up to understand how to make it fun and interesting to control these creatures. We tried things like forming a squad and making them throw balls or battle. But we couldn't quite get to the point where we knew how to make it interesting as a game.

Hino: At the time, when we were creating gameplay in which you throw these characters at the enemy like missiles, Miyamoto-san asked us, “What happens after you throw them? ”So, I answered that they'd surround the enemy and start hitting it. Then he goes, “Can’t they stick to the enemy after you throw them? I mean, I wonder what would happen if they stuck to the enemy’s back or its weak points?”

Miyamoto: Yeah, I remember. So, the team experimented with attaching them to the enemies, and then everyone got all excited like, “Ooh, I threw them and they stuck!” (Laughs) Also, after defeating an enemy, we thought it would be satisfying if you could carry it back home. So, we actually had the creatures carry the enemy, and they looked just like ants carrying a cicada. Once again, a big hit with everyone. (Laughs)

Hino: Lots of ideas were added, like if a creature sticks to an enemy's back, it can attack it, but if it sticks to its mouth, it'll get eaten.

Miyamoto: Even when a creature gets eaten by an enemy, there were also ideas like not letting it get swallowed whole, but instead having the enemy drag it into its mouth to munch on it. (Laughs) And so we eventually added screaming sounds and ghost effects to depict its dying moments to the bitter end.

Hino: In the end, we settled on a gameplay loop in which the creatures would increase in number as they brought the enemies they defeated back, but right before we had a final product, even Miyamoto-san seemed a bit hesitant and said, “I don’t know, I wonder if it’s really a good idea to have the number of creatures grow with each dead enemy. Is it too much...?” But we pushed for it in the end, and said, “We’ve come this far, let’s just go for it!” (Laughs)

Miyamoto: For a brief moment, I wondered, "Are we dead set on doing this?" (Laughs)

But I guess that's how the food chain works in nature.

Hino: Creating a real-life ecosystem wasn't our primary plan, but we did intend to convey a touch of somberness, not just cuteness. Like looking down on a lifelike world from a bird’s eye view. And when you look at the enemies, many have mysterious designs that seem like they'd exist somewhere in nature.

Miyamoto: It's full of unique characters, right? I think the designers played an active role in this game. That's not to say we took an 'art-first' approach. Rather, the game's design was based on what actions Pikmin would perform, so that approach is Nintendo-like.

Hino: Although the character and world design, as well as actions like stick, throw, and carry, had been decided, it took us a while to finalize the gameplay loop. There were various elements floating around and we couldn’t quite fit them together and figure out exactly what the characters should do and what would constitute “completing the game.” In Miyamoto-san’s mind, though, there was a plan to announce Pikmin at E3 (6) in 2001, when games for Nintendo GameCube were going to be revealed.

(6) Short for Electronic Entertainment Expo. An exhibition for video games held in Los Angeles, California, U.S.

Miyamoto: So, as the producer of the game, I pleaded to Abe-san, “I’ll join as a director, so please give me three months. I’ll step down if it fails.” (Laughs)

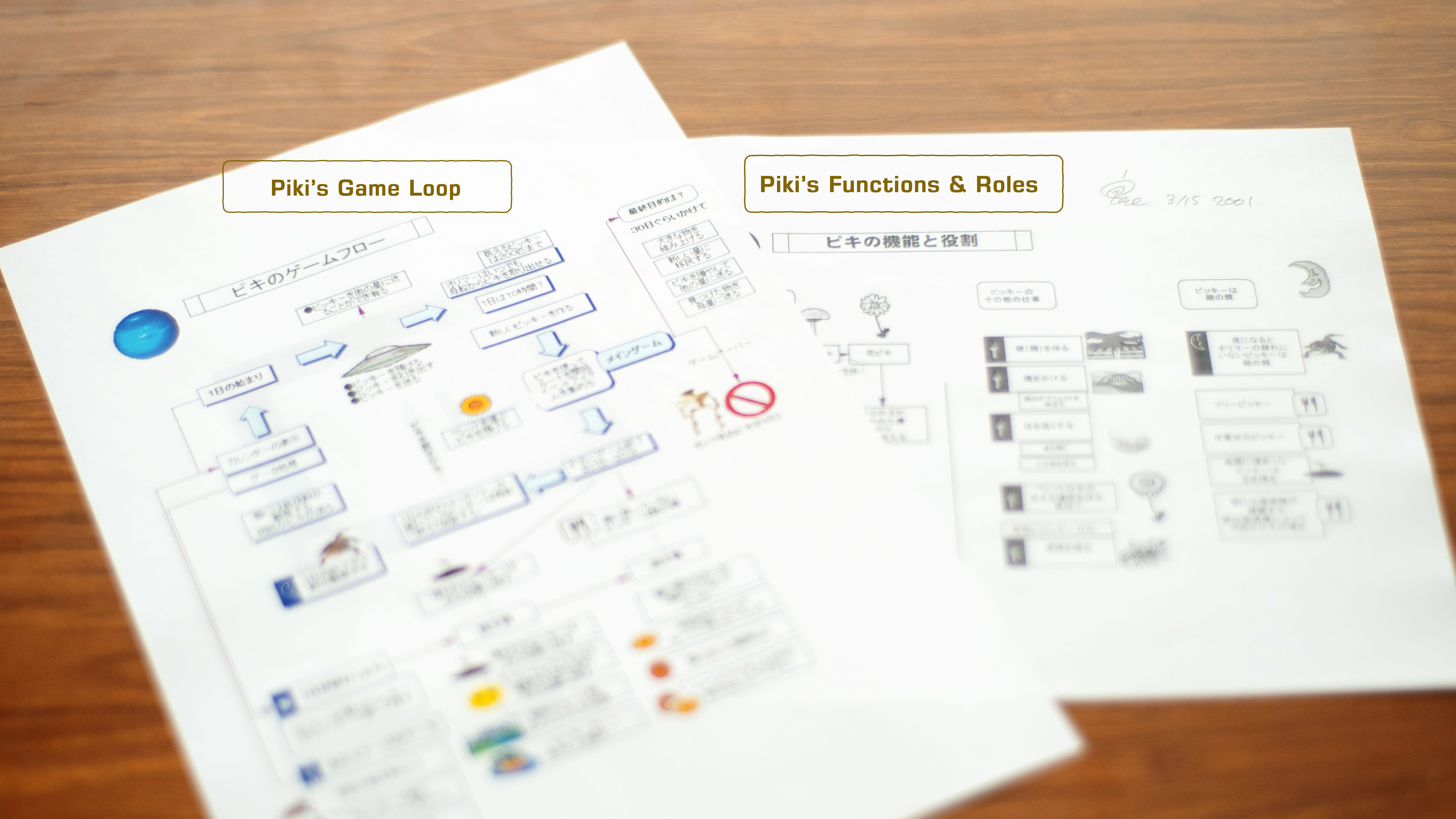

Kando: That’s when Miyamoto-san put together all of our scattered ideas―hardly leaving any behind―into a single game flow diagram. By the way, Pikmin were called Piki or Picky back then, so that’s what you see on this document.

Wow, this is... really interesting.

Hino: It begins with throwing these characters from the squad to give them orders. The goal is to carry the object home. So, the goal isn't to bring a certain number of Pikmin to the end point, but how it works is that you'll need to gather enough of them to be able to carry the objects. On top of that, he shared with us the purposes that enemies and plants serve, how a day passes, Pikmin biology, and the mechanism by which Pikmin grow in number.

Miyamoto: At first, the goal was to lead Piki all the way to the exit. But I didn’t like aiming for a goal set by someone else, like, “You’ll complete the game if you bring 50 Piki to the end point.” I mean, who decided that it has to be 50, right? On the other hand, "X number is required to carry an object" made more sense to me. If you want to carry something that looks heavy, you need more Pikmin. Everyone can understand this concept intuitively. That’s why I started to think about this game in terms of how efficiently players fight enemies, transport objects, and grow their squads.

So, this diagram shows you where each element is located in the game.

Miyamoto: At first glance, this diagram just looks like a bunch of cryptic sentences strung together, but if you follow each sentence one by one, you can understand the program's flow with this single sheet. In other words, nothing other than what’s written here will happen. It always happens with game development. We want to do this, we want to do that, and we end up with lots of new elements. Then the director says, “Well, I guess we'll have to figure out how to fit them all together!” and flees the scene. (Laughs)

Everyone: (Laughs)

Miyamoto: But this diagram is also a declaration that we won't do anything more than what’s written here! Unless we set those boundaries, we can’t develop with so many people involved. I figured I'd better draft them myself before bossing others around. So, I wrote it all down while discussing with Kando-san things like how AI works in the system, whether the processing would be able to keep up, and, if not, whether it could be replaced with other mechanics.

Kando: Only after seeing this diagram, was I finally convinced that it would work as a game.

By the way, Pikmin were originally called Piki, as it says here, right?

Abe: During development, we were using the word “ippiki" to count these characters. (In Japanese, “ippiki” means “one small animal.”) Colin-san (7), who was working with us on the program, heard us counting these creatures and mistakenly thought that we were calling them “Piki.” (Laughs)

(7) Colin Reed. A programmer who was a member of the former Entertainment Analysis & Development Department at Nintendo. Involved in the development of titles such as Star Fox™ for Super Famicom and Metroid Prime™ Hunters for Nintendo DS™.

I see, so he thought the counter “piki” was their name. (Laughs) In some places, I see that it’s written “Picky.”

Abe: That's right. “Piki” evolved to “Picky,” and when deciding its official name, we settled on “Pikmin.” We thought it sounded a bit like "pick me.”

Miyamoto: It kind of sounded like "vitamin" too, so we thought it was good. (Laughs)

I see. So, after this diagram had been made, it all came together well.

Hino: About two months after that, we announced it at E3. But we were actually making edits to the announcement trailer at the eleventh hour. Miyamoto-san would ask us to revise the game footage saying, “I want to fix this part of the script,” and we'd quickly make the adjustments. And so it went, on and on. (Laughs) Miyamoto-san then took what we'd completed at the last minute and hand-carried it on the plane to L.A.

Miyamoto: At E3, I spoke as if the game was finished. (Laughs)

Hino: I thought it was amazing. (Laughs)

When Pikmin was announced, I was under the impression that the development was close to being done.

Morii: But at that point, there was just one stage, as I recall. Plus, it was a layout made exclusively for that show. (Laughs)

Miyamoto: In my defense, I made the announcement because I believed we could pull it off. (Laughs) I was confident that we'd finish the game.

Going back a little to our discussion about the gameplay loop, I believe the term "Dandori" (8) is used in Pikmin 4. Was this gameplay loop, referred to as “Dandori,” already established during the development of the first Pikmin?

(8) A Japanese word that means "to think about planning and efficiency in advance to get things done smoothly."

Miyamoto: Simply put, the idea was something that I came up with while observing ants in my garden... But the reality was a bit more complicated. Even before the Pikmin game came into the world, there were all manner of PC simulations where you'd have to, for instance, choose whether to eat grains of rice or plant them to grow more. I've always wanted to create this kind of gameplay where you manage things. For example, as a manager in your workplace, you think about who should be given what task to get things done. You have a small project here and a large, resource-heavy project there, and there’s this sense of accomplishment when you're able to streamline and manage all of that efficiently. I thought it would be interesting if we could play with this concept in a rich world with many AI-controlled characters.

Abe: During Pikmin and Pikmin 2’s development, we were calling it a “task management game” internally, weren't we?

Hino: We couldn’t find the right description of game genre that could accurately represent the product, so we referred to it as an “AI action game.”

Miyamoto: Games are fun because of the continual trial and error. Pikmin seems to be often associated with its characters and world first, but it does possess fundamental fun as a video game. As you repeat the same gameplay, you develop your own technique, which improves efficiency and results in higher scores.

The fun of playing repeatedly and outdoing your past self, right?

Miyamoto: There were even some players of the original Pikmin game who went for a perfect game without letting a single Pikmin die. That’s a 10 out of 10 playstyle. Even I wouldn’t want to try it; it’s too hard. (Laughs)

Hino: On the other hand, the first game had a time limit where players had to complete the task within 30 in-game days. If they missed, they'd have to start all over again, which felt too long for some people. So, we eliminated the time limits in Pikmin 2 and introduced more Pikmin types and treasures. We also created a catalog and made it a game about collecting things little by little.

Kando: The playstyle changed from “time management” to “type management.”

Miyamoto: That's how Pikmin 2 ended up, but we had multiple discussions on what direction to take with Pikmin 3. The first game provides a deeper challenge, while the second game is broader in terms of content. Players were divided as to which game they preferred, and some people even talked in terms of being either a ‘Pikmin 1 person’ or a ‘Pikmin 2 person.’

Kando: In the early development phase of the third game, we were competing with several programmers to see how many spaceship parts we could recover in The Forest of Hope, from the first game, within the one-day time limit. In the end, we agreed that having that deeper challenge was still more interesting than having a broad range of content, so for Pikmin 3, we went back down the route of the first game.

Hino: We added a “Mission Mode” on top of the main game and designed it so that players could train up their skills to be able to complete the main game more efficiently. I think that's when we started to use the term “Dandori” to describe the gameplay, right?

Kando: That’s right. We realized that task management games give a sense of accomplishment that even people who don't play games can relate to. It's like when you’re doing housework or cooking. Once you get used to it, you start to think about Dandori and then you get things done more efficiently. I think that process is fun.

So, that’s how you came to describe it as a Dandori game. I can see that each title in the series has been thought through so that the fun of management stands out.

Miyamoto: Looking back at it now, I think there was always this sense among the developers that we should return to the direction of the first game. ...But ultimately, once the third game was released following the direction of the first game, there were some people who said they preferred the second one. (Laughs)

Kando: So as a result of numerous considerations over a long period of time, the fourth game welcomes people with various different tastes. There were completely different takes on how Pikmin games should be between those who liked the style of Pikmin 1 and those who preferred that of Pikmin 2, so maybe Pikmin 4 can finally bring the debate of 'Pikmin 1 people' versus 'Pikmin 2 people' to an end. (Laughs)